Source: Jam Hotel Instagram

Brussels is a city of grand townhouses and art nouveau. Yet plonked in the middle of the Belgian capital, on a nondescript street corner, has appeared a hotel that looks like downtown LA had it been swallowed by lava. An old 1970s art college has been redesigned and rebuilt, by people who usually make film sets, to become the oddest, most fashionable, most affordable stopover in Europe.

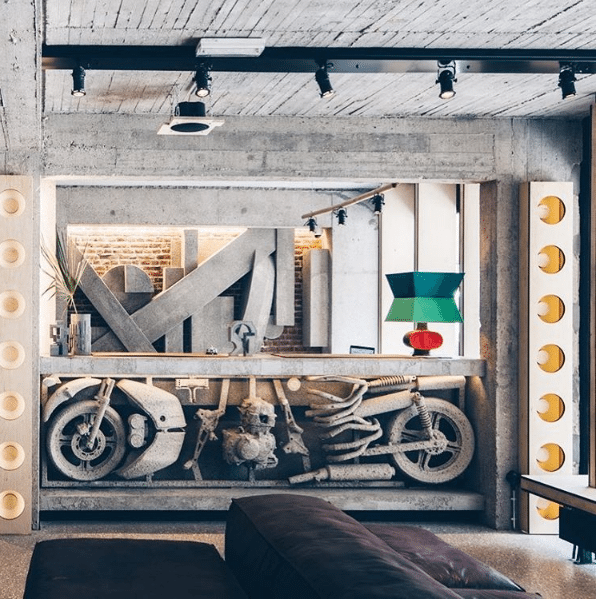

The reception desk is held up by a pair of motorcycles dipped in concrete – above it rest maquettes, Paolozzi-like little bricks of angles and texture. Three guests under 10 years old leap joyfully between leather sofas and concrete benches while they wait for their parents to check into one of the Supra rooms which sleep five, one up by the ceiling, in what they call a “cabine bed”.

In my bedroom, the roughness of concrete and cement is softened by elegant plywood, glowing in the bright light of those office-wide windows. To the right of the double bed, above a built-in sofa, a ladder climbs up to what looks like a cupboard. But slide the doors open and here is the promised cabin bed. Its sleek neatness is pleasing, its promise of claustrophobia less so.

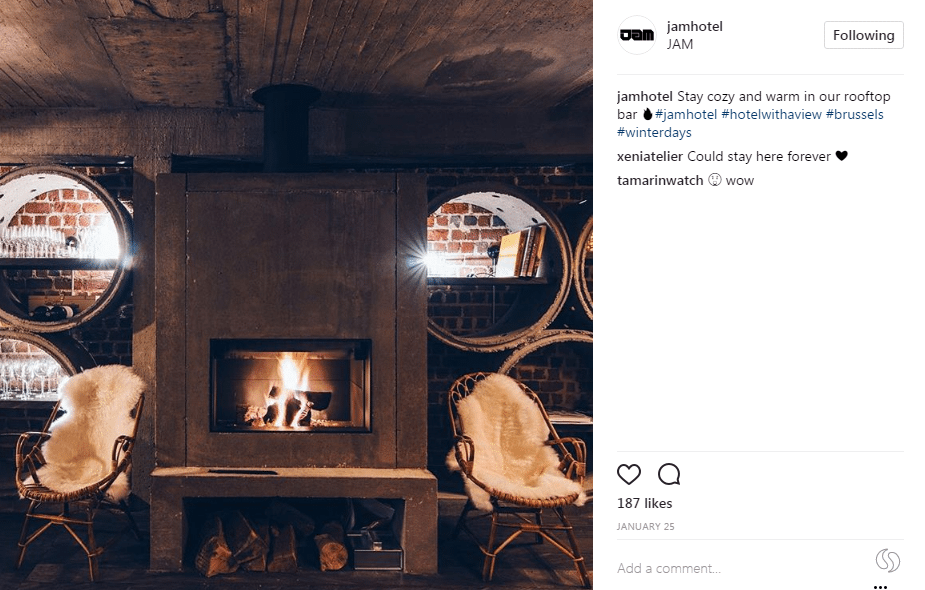

In a place where every corner hides a new, brutalist thrill, this is the most exciting aspect of the Jam Hotel. As well as the family rooms – for up to six – there is a boutique dormitory, a vast room of bunkbeds and Japanese-style cabins, their plywood doors in flashes of primary colours, and available for €18 (£15) a night per person. Upstairs on the roof, there’s a pool. Nobody would call it a swimming pool. It’s a long rectangle of water designed for plunging into on hot days, or for submerged drinking at night. The sunset is pink and yellow in the rooftop bar, which is alive with handsome locals from 6pm.

Huge slices of concrete tunnelling, once sewer pipes, decorate the wall by the terrace; at the other end of the room, windows look out on to a wildish garden. You see the trickling greenery from the restaurant, too, an old car park where lamps made from drainage connector pipes are held in place by luggage straps. Wood offcuts become cubist collages on the walls. The food is Italian and good: vast bowls of pasta in the evenings, with a griddle for guests to fry their eggs at breakfast. Which is helpful because, at times, the staff can be almost as brutal as the design. This is not a “May I take your bags to your room?” kind of place, or even a “sure, we have a plug adapter you can borrow” kind of place, but it’s almost better for that casualness, which suits the brilliant, bonkers austerity of the building.

This is one of a group of alternative Belgian hotels that are run by Jean-Michel André, a hotelier aiming to innovate the industry. They offer “experiences”, he says. I note that as well as bikes, there are skateboards for guests to borrow.

The interior designer, Lionel Jadot, came up with the hotel’s name – he was thinking of traffic. He said he treated the ground floor like a “big constructivist sculpture” and it’s an odd feeling, emerging from this romantic bleakness into streets of neo-classical architecture. In one direction is Place Stéphanie, which spiders out towards a strip of fashionable shops, with signs that urge you to Instagram yourself beside their displays and drink coffee among the handbags. In the other direction, a 20-minute walk downhill to Place du Jeu de Balle, is the Old Market. It’s been here since 1854, a maze of blankets thrown down and strewn with masks and books and bartering old men. If you kneel down and dig through the cardboard boxes, it’s even possible to find vintage ceramics similar to those that appear up the hill, like paint splashes on the hotel’s grey concrete surfaces. However, if you’re attempting to recreate the Jam’s interior, it will take a little more than a morning at the market.

Dorm rooms cost from €18 (£15) a night, while a room sleeping six costs from €150 (£128) at Jam Hotel, Brussels (jamhotel.be). Eurostar operates up to 11 daily services from London St Pancras International to Brussels, with fares from £29 one way (eurostar.com)

Source: The Guardian, April 2017

Source: Jam Hotel Instagram

Recent Comments